In Japan dynasties are somewhat less durable than in China, possibly because of powerful noble families, but on first inspection the time course is the same.

Go to a world map, a good old Mercator projection with north along the top. Turn it upside down so that north is at the bottom. Now take a gander at Japan. The Japanese archipelago is shaped like a dragon. See if I tell the truth. For one thing, the image of a dragon is rather an understatement. This is a land of fierce fighters. Not that long ago, there was an earthquake in the country. It was decided to send the Japanese navy to conduct a rescue operation. The time between the earthquake shock and the last ship casting off was forty-five minutes. My mouth goes dry just thinking about such readiness for trouble. So, Japan looks like a dragon and is one. Italy looks like a boot (right side up this time), and Italian leatherwork is legendary. I cannot imagine how the most ardent conspiracy enthusiast can tie these together. Oh, there’s more, maybe when we’re younger.

When I run into things like this, the words go through my head, “It’s all a hoax, this reality thing. Such coincidences are impossible to explain. Reality is just noise in our heads.” But getting back to reality, consider the survival pattern of Japanese dynasties in figure 37.

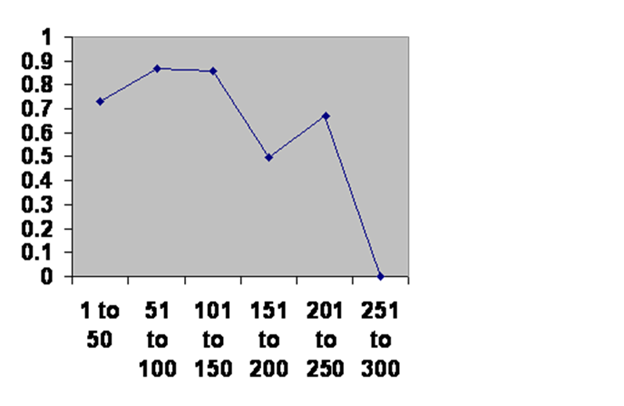

Here is the survival experience of Japanese dynasties. The vertical axis is the chance that a dynasty of that age will survive another 50 years. The horizontal axis is the age of the dynasties.

Fig. 3718

By now you are thoroughly familiar with the axes. The probability that a dynasty (yes, we are talking dynasties now, not civilizations as in some other parts of the world, but have a care. This will be subject to interpretation.) will survive another fifty years is on the vertical axis graphed against age on the horizontal. The result is most impressive, although no match for China in stability at least in the first analysis of China.

For one thing, notice that over the first fifty years the chance of survival rises. Remember there was a lot of that in Egypt. That is the hallmark of selection, the more resilient regimes have better survival chances than the average. Japan is an archipelago. Although it is long and thin, there is not the isolation of the desert. A kind Swedish woman once remarked to me, “In the old days water did not separate people; it brought people together.” If anything, it would be the precipitous mountains of the interior that would limit travel. Instead (drawing on my almost total lack of knowledge of history) I suspect it was the noble families, the bureaucrats and court officials who limited travel. Potentially they had the clout to challenge a new dynasty but not an older, better established one. Survival chances improve if one can just manage to get a little older. Again, this is an initial impression; we shall be returning.

Now notice the notch. It occurs at the same time as the notch occurs in China. I’ll not say “exactly” the same time, since we have lumped things into 50-year increments. But it is as close as we can tell, and that goes for both analyses of Chinese history. And the notch is deeper than it was in China. I suspect that when lowered fertility leaves the imperial dynasty vulnerable, the same powerful families still kettle like so many waiting hawks and vultures, looking for a time to stoop. In such an environment it is not surprising that no Japanese dynasty makes it past the 300-year brick wall on this analysis.

The timing, indeed the very fact of the two notches makes it no stretch to infer an identical process in both. Also, notice the comparison with the history of Lower Mesopotamia, how similar they are. If you are not threatening to pillory me in public or offer serious bodily harm, you are not attending so I’ll say it for you, “Are you mad? There is nothing remotely resembling your “notch” in Lower Mesopotamia.” Oh, it’s there all right; let me point it out.

But first let me digress and mention a wonderful painting by Rembrandt. It shows Belshazzar at his feast looking at the handwriting on the wall. That man is not scared. He is not even pale. His expression could mean, “I smell something dreadful.” Pallor is such a routine expression of fear that WW I soldiers were called doughboys. In the book of Daniel, Belshazzar is so frightened that he loses sphincter control and evacuates on the spot. My mother used to use the expression “pooped on the parapet” to describe somebody so afraid that he disgraced himself. There are some women in the painting, but only one other man, and he is old, older than all get out. The civilization falls when everybody is too old to fight, if I follow Rembrandt’s sense of it.

So, the moment of conquest is the result of a factor in the city. It has nothing to do with events in the tribe of warlike barbarians or the sophisticated society that moves in to take over. Whatever group comes in of course has to be big enough to be more than a nuisance. They are already part way through their cycle of growth and extinction. And their position on this time line has nothing to do with factors in the city; it is random with respect to that.

So, let us assume no notch. In fact, assume every society lasts 300 years exactly. At a random time, the society seizes Mesopotamia, finishes its run and dies. We will then do a fake random distribution. One society lasts 50 years, the next between 50 and 100 and so forth. This graphs out as 1, 1, 1 and so forth. But add another row of 50-year intervals starting at the 50-year mark of the new row. The scores are now 2 except that the final 50-year increment is one shy and remains one. Keep adding more rows until the added row is only one fifty-year segment. Summate them, and obviously the sum in the first column will be the biggest, as it receives a count for each iteration. The final increment gets only one count, and in between the falling life expectancy is a straight line.

But the line in fact curves downward. This is true in Lower Mesopotamia, the group with the Mayans … you can even see it in Egypt. But if you add the notch, then you get the curve. On the other hand, you remember castrating all those Chinese boys. Everybody except the imperial household is an effectively and wholesomely inbred peasant. Every dynasty starts out at the beginning of its cycle. The notch is visible. Japan did not have rule by eunuch, but the noble families must have had varying fertility. The family with the most capable members would tend to win the competition to become emperors. They would have been closest to the beginning of their cycle. It wasn’t as strict and clear cut as in China, but it was close enough to make the notch visible. In fact, occasionally a Chinese emperor might take a low-ranking wife. That would give my proposed mechanism a kick where it hurt if not demolish it. I shall have more intense groveling to do soon.

So yes, the populations seem to be following the same mechanism; the difference in the survival experience is superficial.

I used to suggest that some historical research could be done here. Have somebody (yeah, it’s easy to ask somebody else to undertake years of tedious study) go over the fall of every dynasty in China and Japan. Assign a cause to each collapse. Do enough lumping or splitting so that each cause has a reasonably large number of victims. It might be possible to see if there were any differences in the reasons for failure in these two kinds of time. But I have now made an attempt to do just this with results I find unimpressive. Maybe it’s not worth the time.

Bearing in mind my extreme ignorance, but referring to books on Japan given me by someone who knows about the country, there was a hereditary class of warriors called samurai. They got a stipend from the government and usually were loyal to some powerful person. But sometimes a samurai would lack a master. The warrior still got his stipend and still did the training expected of all. These were the ronins. Without a master, they could move about with relative freedom, and if one ran across something that offended his idea of proper behavior, he had the authority, the weapons and the training to put things to right. In European tradition, this would be a knight errant. The European knight errant sought out adventure and was more or less on the lookout for courtly love.

The ronins were real, knights errant pretty much a fictional device, with one possible exception. The Battle of Badon Hill took place in the late fifth or early sixth century. The Britons consisted of a peasantry of people who went back to the middle stone age, and a more newly arrived aristocracy of Celts. The Celts kept their pants on, and they did not go about philandering with the peasant lasses. That means there is no surviving genetic trace of them. No problem: folks just changed the meaning of the word rather recently. The land was being invaded by Germanic Saxons, and at Badon Hill the Brits sent them packing. Later the Saxons came back and made their conquest good. If you listen to the Saxon descendants, of course, there was no Battle of Badon Hill. The invaders simply walked right over what was left of Britain after the departure of the Romans. It does smell like a case of history by the victor.

Our experience in other places in the world is that the defenders should be invincible unless they have a fertility problem. So sometime, no doubt in the sixth century, time ran out for the Celts.

When they looked around, they could see that there were no babies. They were all old. It would have been most reasonable to wonder what had become of the next generation and how to fix it.

There is only a whiff of circumstantial evidence, but it would have been understandable if the warriors went around looking for the cure. This would have not resulted in much interest in Britain. Everybody could see the difficulty. But then, just maybe, a few of them went to France to ask around.

This would have been astonishing. In the dark ages you could go to France and not see anybody for days. But they would have run across people from time to time, and the reaction must have been, “You came here from where, looking for what? Are you mad?” How many traveled together? When I was a boy scout, we would go camping in Florida wilderness. There would be a watch fire, and somebody would stay awake to tend it. A man alone at night in the woods would be vulnerable were he to sleep.

All was forgotten in Britain, but centuries later in France, a poet named Chrétien de Troyes, 1135? – 1185?, wrote some stories of King Arthur. There had been whisperings of the enigmatic character for some time, but Chrétien put in the story of the Holy Grail. Somehow it got remembered after all those years. At least Arthur’s knights tried.

The importance of the Grail is not its origin or history as an object. It isn’t an object at all; Arthur’s knights were probably aware of that. The importance of the Grail is that it is the cure for the depopulation that destroyed Arthur’s realm. It is a concept. You are learning it right now.

Well might one wonder whether the Celtic refusal to use their status in order to tumble every attractive female they encountered, (In college I remember hearing, “It’s spring break; screw anything that moves,” Yankees, you know) was part of their impact. But on the issue of, “It matters whom you marry,” they were dead on. How they got that right is to me totally opaque. It’s another of those impossible coincidences.

As with China, we shall consult another source.19 This information was put together by Peter Kessler and placed on the internet. I shall be going over the time between the start of good historical information in 346 AD and the entry of Japan into the modern world in 1868. I surfed until I put together some of the problems the regimes dealt with and periods of time regimes lasted. 0 – 50 years: Europeans were found to be filthy, disgusting and bellicose, failed invasion of Korea, armed revolt, infant emperor. 51 – 100 years: Emperors becoming Buddhist and abdicating, smallpox, clan rebellions, a Buddhist priest attempted a coup, the land had been split now reunited, shogun revolt, three Mongol invasions, country split. 151 – 200: War over Buddhism, murder, earthquake, empress abdicates, civil war, European conflict. 301 – 450 Clan fights, cloistered emperors, shogun resigns.

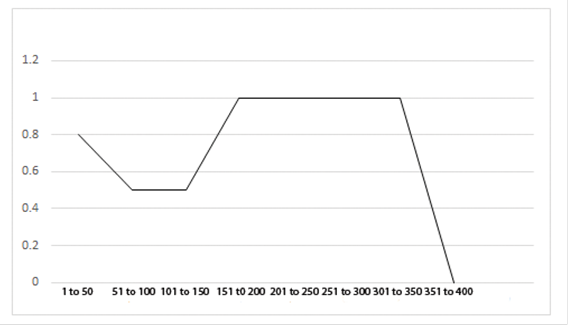

In figure 39 I graphed the Japanese experience in the same way as I did other countries.

Here is the survival experience of Japanese eras. The vertical axis is the chance that an era of that age will survive another 50 years. The horizontal axis age of the eras.

Fig. 3920

Well that knocks it all into a cocked hat. It does not remotely resemble the earlier graphs. The notch is not present; it was a single 50-year interval. This shows two adjacent low intervals. And there is the final period which, goes right past the apparent brick wall of 300 years. The only reason to choose the first analysis over the second would be if one were data shopping. So, I don’t know what we are looking at here.